Emerging names in Singapore’s art scene to look out for tell us more about their diverse practices.

Hi Anna! Tell us a little about yourself.

“I am a 21-year-old student currently finishing my final year at the Ruskin School of Art, which is part of the University of Oxford. My dad is an architect so that definitely had an influence on me as a kid. I was a menace growing up and would draw on table cloths in Pepperoni’s or rearrange objects in people’s homes. I guess my parents noticed my interest in visual art, and thankfully they nurtured it.”

What have been the main sources of inspiration for you? Who or what has influenced your path as an artist?

“Definitely the people around me. Whether through the stories they tell me, or just general fun facts and everyday banter, (all of it) ends up influencing my work in some minute way. Being in university helps because I meet peers from all over the world who study different subjects other than art and I just end up learning so much through conversations with them. This, in turn, has made my work much richer, instead of just visually pleasing.”

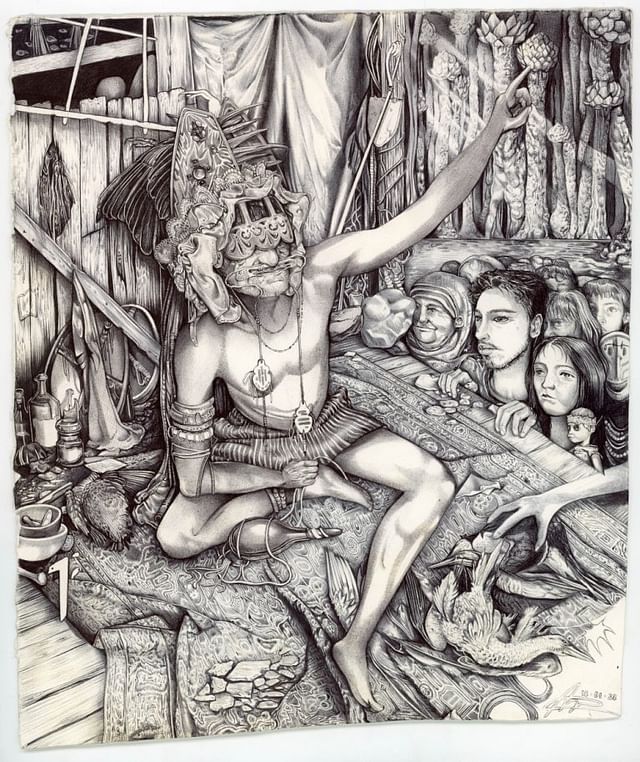

I think we also have to talk about the elements of surrealism in your works – is there a story behind them?

“I like to think of myself as an inspiration magpie. Anything that visually stimulates me somehow appears in my work. I gradually piece together the things and images I collect subconsciously before they materialise in my artwork. My main motifs include birds, tudor ruffs, orchids, long necks and recurrent forms. Listing them out here has made me realise there really isn’t anything that ties them together. I don’t have a complex reason as to why I include these motifs; I simply find them beautiful, and I have an urge to paint beautiful things in the weirdest fashion.

One of my biggest surrealist influences, the Polish painter Zdzisław Beksinski, believed that an object may have one fixed association for the artist, but when faced with an audience of hundreds, becomes a complex interplay between multiple associations. I live by this.”

Credit: Anna Du Toit

Anime and fairy tale characters also seem to be a key motif in your works – what’s your fascination with them? Who or what are some of your favourite characters and why do they resonate with you?

“I love hard world-building and fantasy – anything out-of-this-world and extraordinary makes me happy. These fictional characters are always portrayed in such different styles too. It’s a fantastical reinterpretation of the ordinary, and I love it. Manga such as Blame! and Akira refashion architecture and cityscapes whilst characters like Baba Yaga and Quelaag from Dark Souls reimagine the possibility of other beings existing. I love exploring the minds of storytellers and we definitely need more of them.”

How has the response been to your artworks so far?

“I am so grateful for the connections I have made with others, whether that is within the art school or through my Instagram account. Just meeting kindred souls with a love for what I do and hearing the positive things they have to say is definitely the most rewarding part of being an artist. I am still learning so much, and this process of discovery and engagement is something I will continue to do forever.

One of my most memorable moments was setting up a booth within the artists gallery at the London Comic Con last October. Interacting with cosplayers, selling my work for the first time, as well as meeting countless other artists, was such an amazing experience. This led me to set up my own online art store (https://oo0o0ooo.bigcartel.com/) through which I have continued to sell my work as well as do private commissions.”

What else are you working on or excited for in 2023?

“Since it’s my graduating year, I want to churn out as much experimental work as I can before my final-year exhibition in June. I am currently trying out sculpture and alternative printing methods, which are relatively new mediums for me. I would like to become more interdisciplinary with my work, and hopefully collaborate more with others, both in Singapore and the UK.”

London-based creative multi-hyphenate Bart Seng is a visual artist, fiction writer and curator. His medium-transcending approach is grounded by themes from his own personal life – like self-fetishisation, fantasia, ambition, human connection and failures. Part of the prestigious Dazed x Circa’s Class of 2021 programme, Seng’s film Out in the World was shown on the world’s largest public screens in Piccadilly Circus, as well as in Tokyo and Seoul.

More recently, the film, which follows a miniature figure attired in black fetish attire juxtaposed against a Lazy Susan in a Chinese restaurant, was also singled out by acclaimed fashion photographer Nick Knight for its singular vision in his ShowStudio short film critique series last Feb.

Credit: Bart Seng

Hi Bart! Tell us a little about yourself.

“I realised I wanted to make films at age 15 and worked really hard to get into Ngee Ann Polytechnic’s FSV (Film, Sound and Video) course after secondary school. I remember at that time, nothing mattered to me more than achieving the GCSE score needed for film school admission. Then, I studied photography for my BA course at the London College of Communication, because I was interested in expanding out to different mediums, concepts and aesthetics. While film is always my first and biggest love, the photography education I had opened my mind to a lot of different possibilities in terms of art-making, and I have been very lucky to explore all these different strands of expressions since. Which is also great because I am such a disaster (at being sociable), and so one of my reasons to be an artist is to allow myself to open up bravely.

My inspirations are really varied but I remember the ones that remain constant throughout all the seasons of my life: Joanna Newsom, Edward Yang, Radiohead, Christian Petzold, Jafar Panahi, Francisco Goya, Torbjorn Rodland, Lars von Trier, the sport of MMA and Lee Chang Dong.”

We first got to know of you through your photography work, but now you’ve also expanded into filmmaking, visual arts and fictional writing. There’s a lot to cover – how should we understand your practice?

“I think these different mediums are all equals to me, like I am clear about why I use photography/still imageries for certain projects, as opposed to moving images, as opposed to literature and so on. Similarly, you can say that about ‘curating’ for Kawaii Agency (a curatorial project started by Seng and Juliusz Grabianski that focuses on ‘yassified’ Gen Z aesthetics and digital culture) – that is also a mode of art making, although it’s mostly an exercise in marketing for me and my co-founder Juliusz.

But anyway, I think these mediums are all equal to each other, and the way they express things are unique in their own ways, but the feeling (for lack of a better word) they are chasing after when encountered by an audience is the same throughout everything I do. That feeling is the desire to be understood so completely and so deeply and so affectionately.”

Your website says themes covered in your work are self-fetishisation, fantasia, otherness, ambition, human connection, myth and the neoliberal capitalist singularity. What draws you to these themes in particular? Is there a personal story behind your interest in them?

“I feel like these themes are almost autobiographical. They are all things that arise from my own life, my position within the world, the things that I am most excited about, and the ways that I see/understand things.”

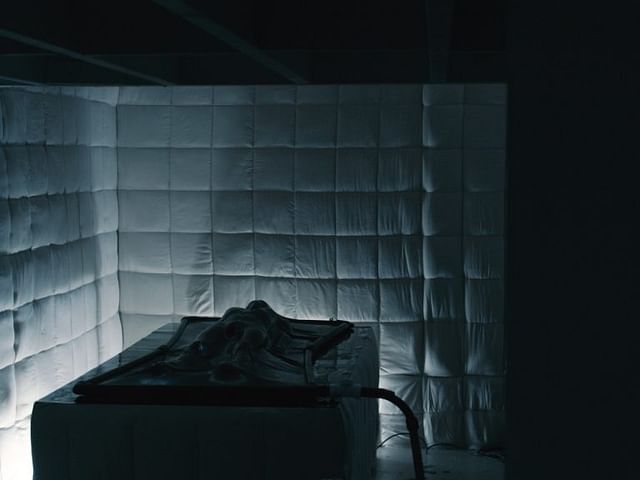

Credit: Bart Seng

How do you manifest those themes through your works?

“My favourite work, ASMR, combines some of these ideas in a photograph, like we are watching the fantasy immersion of a figure who has turned themselves into a fetish object, and this fetishisation connects it with the textures of the rest of the business suite (that the photo is set in), which in turn helps to frame the fetish figure in a kind of modern day capitalist mythology.

It speaks of fantasy, othering yourself, the role of fetish materials in capitalism and of course, the mystery of what is playing in the gimp’s headphone. Another example is my (legendary sculptor) Rodin recreations, where I ‘cast’ friends as Rodin sculptures but using the more kinky method of mummification to do that. The choice of Rodin speaks of my own ambitions as an artist, but the outcome of these exercises always puts that ambition on the path of a joke.

I also like considering the interconnections between people, things, histories and experiences in the artwork, using them as part of its internal dynamic and lore. Like in meme #2 (pictured), where there is drama being played out between the ominous hand and the hooded person, the negated face and the ‘girly’ face from the BL (boys’ love) manga, the reconstructed image and the manga reference. I don’t know what exactly should one interpret when seeing these relations but I like putting them together and I really get a laugh out of it.”

Gimps (a person who derives sexual pleasure from being hurt or treated badly) appear to be a recurring motif in your work. What spurred your interest in them? What do they represent to you and why are you obsessed with them?

“I have a major soft spots for them because being a gimp has a historically insulting insinuation, and yet some people willingly throw themselves into that role, allowing it to negate their own sense of self in order to serve (someone else).

I think there is a lot we can learn about gimps especially in the current self-obsessed, hostile and competitive socio-political realities where people feel more and more powerless in various ways… for example, (in answer) to the coercive (push) for capitalist growth, the gimp offers radical passivity… Against the injustices of exploitation and trauma, the gimp offers strength in surrender.”

Credit: Bart Seng

There is often a sense of offbeat surrealism in your works. Can you tell us more about that?

“I like to explore conflict in the various layers of making art, from the narrative to the visual style to the ethics of the work, because I feel like art gives us this very special opportunity within our encounter with it to ‘straddle on two boats at once’, when in real life we are often forced to have to act only in one way or another.

Likewise, the process of making work lets me consider a particular conflict in my own life through a wider range of seemingly disparate lenses at the same time. My short film Out in the World (which follows a miniature subject adorned in black, veneered fetishwear as it sits upon a Lazy Susan – a commonplace fixture in Chinese restaurants) creates an ambiguous relationship between the two parties (the fetish figure and the Orientalist setting) such that it’s not clear who is looking and who is performing.

There is a conflict at the core of the work, but it is also a conflict that originated from our collective imagination of Orientalism, taboos and hierarchy. The juxtaposition makes the conflict less straightforward and more funny. My lighting choices are designed to augment a sense of magical realism in my pictures. I prefer magic realism to surrealism because there’s just a lot more tension to introduce so-called magic in what appears to be reality. The lighting allows this sensation of uncanniness to permeate in the image.”

What are you working on next that you can share with us?

“I am finishing a new short story called Gimp Theory, working on a new photographic project and hopefully starting the process on a new short film. I may or may not be curating a programme for a film festival too.”

DANIEL CHONG, 27, SCULPTOR AND CURATOR

Credit: Daniel Chong

Chong’s sculptures and installations tend to bring a smile to the face – imagine a pair of jeans filled with “milk” (it’s resin) and spilt Fruit Loops cereal, or an oversized biscuit with a giant chunk “bitten” out of it – they are often commonplace, everyday objects that are injected with a sense of playful humour and whimsy by the artist to disrupt traditional understandings of said objects.

It’s an approach that seems to extend to his curatorial work as well – cue the ongoing Stranger(‘s) Touch series, which he co-founded and which is billed as an “art project disguised as a retail brand”. As an emerging curator, Chong was the receipient of Objectifs’ Curator Open Call 2022 and also co-curated Bad Imitation, one of the buzziest shows at last year’s Singapore Art Week.

Credit: Marvin Tang

Hi Daniel! Tell us about your journey as an artist. How did you come to to be in the art industry? What have been the main sources of inspiration for you? Who or what has influenced your path as an artist?

“It’s funny you ask this. Growing up, I wanted to be a scientist. I never had any interest in art. It was actually learning about conceptual art that kickstarted my journey into the industry. I was literally on the Wikipedia page for conceptual art and I thought to myself, ‘Hey, I could do this too!’, and I didn’t even mean it condescendingly. I was so piqued that art didn’t need to be created by the artist, and that having a unique enough thought could be considered art. It actually gave me a lot of hope, I was excited to try to make this ‘art stuff’ for myself. And so began my descent into the vastness of the art world.

Who influenced me were actually a lot of women artists. While I studied and understood the importance of many male artist like Sol LeWitt, Jackson Pollock and what not, but I admired artists like Doris Salcedo, Cornelia Parker, Eva Hesse, and many many more. I always enjoyed how they created works with a different sensibility than their male counterparts. It isn’t entirely a feminine sensibility, but perhaps the awareness that their works could be read through the lens of their gender and navigating with the spaces outside of their work. And because of that I find their works having more interesting layers. People often enter their works with multiple points of revelation or marvel. Their works are like onions – with layers and layers, conceptual, material and historical that can be peeled open.

But what influences me, well right now at least, has less been about the arts but more about myself as a person. Maybe it was about a year ago that I stopped really trying to find my voice within the discourse happening in the current space, but instead find honesty within my own experience. I tell people I’ve kind of figured out my artistic language. I’ve spent years understanding the vocabulary, syntax and grammar of it, and only now am I am I trying to say things in this language. I’ve been very fortunate to have support for my rather eclectic yet unique perspective on the world, with my works mirroring certain fascinations I have. But now I think I’m only starting to well make works that only Daniel can make. Or continuing the metaphor, say things that only I can say.”

It feels like there’s often an emphasis on playful textures and humour in your works – is that intentional?

“I would definitely say its intentional. Some of it is spilled over from me actually having fun while making art, but a lot of it uses humour as a layer to the work. I think a lot of the world is pretty stupid and funny if you really think about it, especially in this day and age. And by extension, this perspective influences the way I make my work, consciously or not. I really see it as a by-product of the world I’m in.

However, how my use of it goes back to having those layers again. I enjoy works that can hold multiple feelings. I like that, similar to people, these objects can hold space for complexity. Something can be sad, and funny, or fun, yet poetic. And it’s often those layers that make a single object able to hold so much space, seemingly beyond its small physical foot print.

These complexities allow people to have more than one access point to my work. It’s not always humour that gets across. I remember someone telling me that my works always seemed violent. People often gravitate towards what they want to see more. I try to think of humour as an easier magnet for people to lean on, but there are definitely a mix bag of emotions layered between within each work.”

Credit: Marvin Tang

A lot of your works have also built narratives around everyday objects such as plastic storage boxes, snacks, soap bars. Why are you so drawn to them?

“I still can’t quite articulate why, but there is a class of everyday objects that just sits in the back of our brain. I keep saying this but we spend a lot of time with these objects to a point where they’re essentially ‘phased out’ in our brain. We don’t really process them actively. A good metaphor would be the ‘invisible gorilla test’. It’s a test where people watch a video and completely miss out a gorilla walking across the screen. I want to be that gorilla. I love working with commonplace objects precisely because they hold the space for this giant hulking gorilla to infiltrate… These objects have that unique ability to hold these new ideas, and well, my own version of that invisible gorilla – be it me pointing the invisible gorilla out to people or me creating my own version of it.

Also I see these objects as having that potential to change not just how someone feels in the museum space, but how they feel about that object. My friends often send me pictures of things found on the road and joke that I made that. But that process, of having them associate these objects to potential artworks, is exactly the kind of subtle infiltration I love. And I think with each commonplace object I use, I hope to nudge the way people examine their surroundings.”

You’re also a curator – how do you balance and/or separate your artistic practice from your curatorial one? What is the relationship between the two for you?

“I actually never really see (my art and curatorial work) as separate entities. In some sense because in my mind, the process of making something curatorial comes from my inability to explore something in my artistic practice. That’s why I always frame it in language. There are some things that are just easier to explain in a certain language and I see my curatorial practice as sometimes a better ‘voice’ to explore certain ideas. How I feel that it benefits me is kind of like how someone who is bilingual just has more ways of expressing something. Often blending and bleeding the artistic and curatorial creates a nice feedback loop.”

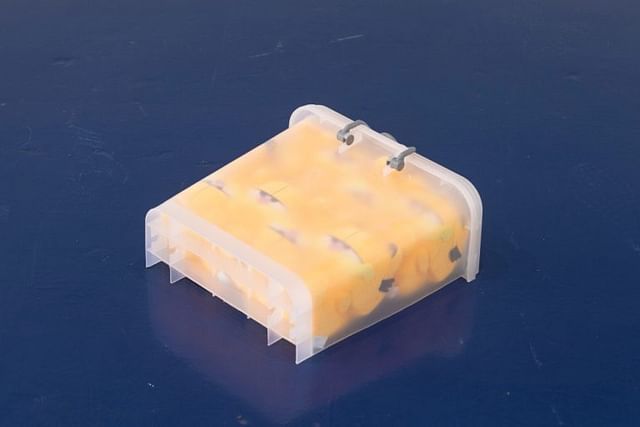

Credit: Daniel Chong

There are also often ephemeral and perishable elements embedded in your work such as lollipops and candy. What’s your fascination with them, given that they likely add additional difficulties to manage?

“I love things that aren’t permanent. There is something beautiful about materials that have a clear life cycle. In some sense that life span or life cycle becomes conceptually poetic. For example it could like about literal decay… but it also could be about the need for constant care, as seen in this work (pictured above: My tongue traces blood splatter, fluid for fluid, each drop swollen into damp chocolate), where I (simulated) blood splatter from a crime scene with chocolate that I (personally) licked.

What ephemerality does it gives an added dimension of time to sculpture – it’s another tool that we can use. I see it as just another material. It is almost on the same level as titles to me, it’s another tool to get your point across.

People also ask why I make such works despite of such difficulties, but it’s precisely this difficulty that I want to bridge to the audiences. That understanding of difficulty in impermanence is so powerful. In that quick though audiences already understand that the work isn’t static. I like that audiences can imagine it rotting, decaying, melting, changing, all without having to actually witness it. The lifespan of the work doesn’t need to play out physically in front of the viewer but already does so in their minds, and that’s somehow quite powerful for me.”

What are you working on next for 2023?

“I’m actually planning to make a video this year! Similar to how I see my art practice and curatorial practice as different languages, I’ve been thinking for a long while what the language of moving image can do for my practice. A lot of my work is already somewhat performative, in that people can imagine an event having happen. So the move to exploring video feels natural for me. Alongside continuing my sculptural explorations into absurd intimacies, I’m really looking forward to producing a video where I become a plant! As absurd as it sounds I swear it’ll make sense when the video is made.”

VANESSA LIEM, 20, PAINTER

Credit: Vanessa Liem

Rising Singapore painter Liem may only be 20 but to date, she’s picked up a gold award in the Emerging Category of the prestigious UOB Painting of the Year in 2019 and staged two solo exhibitions at Cuturi Gallery, which represents the artist. Liem is best-known for her introspective paintings, using an uncanny combination of colours, an unflinching presentation of the female body and distorted, alien-esque proportions to manifest her inner worlds.

Hello Vanessa! Tell us about your journey as an artist. How did you come to to be in the art industry? What have been the main sources of inspiration for you? Who or what has influenced your path as an artist?

“Hello! I think social media, especially instagram has always been helpful for me introducing myself to the art industry and vice versa. I would find a lot of local and international artists there. And slowly, I would go to different shows that I saw were posted and keep up with the art scene. I think the main sources of inspiration for me would probably be other contemporary women painters. Looking at other paintings helps me with my own, the way that the body is rendered, what kind of colors they use and so on. It’s sometimes very refreshing to look at other works that are super different from yours, just to take a breather.”

Your biography says your paintings are “surrealistic depictions of the oppressive weight of existence, particularly hers.” Tell us more about this. What’s your current state of mind?

“I go through phases, like everybody does. During the time period when I made my second solo show, For the Time Being, it was really easy for me to slip into that depressive state of mind, where I just felt really detached and alone. That feeling of bad mental health – it’s always going to be there; it’s not really a matter of making it disappear, it’s more so how we come to terms with and deal with it. Currently, I feel better which is good, it’s still there, it’s just not really in the forefront of my brain right now.”

What draws you to surrealism?

I think surrealism has a lot of aspects that are rooted in reality, but changed in a way that makes it feel less familiar and less comfortable. That balance between recognizing what is happening and not, gives quite a strange and unsettling feeling. I really like that. By changing the things that seem like the norm, it makes you think about the world that we are living in now, our mundane everyday lives and what we already have.”

Credit: Vanessa Liem

I’d like to talk about the colours you use as well. How do you use colour to emphasise what you’re trying to achieve or message to the audience?

“I love to use very vibrant and saturated color to discuss somber topics. And to use very synthetic-looking colors to paint natural things, like nature or the body. I think the color palette adds to the surrealism or fantastical element in my work, where again, we know what those things are but they don’t look like it. I think sometimes, I also use color to add satire in my work; the disconnect in using bright colors in very depressing scenes can add an uncomfortable humor to them.”

The naked female body seems to be a central motif to your practice. What’s the story behind it?

“It’s natural for me to paint the female body because I am one, I grew up with one and have an intimate relationship with one. I see it every day, naked or not, so it doesn’t strike as unusual to paint a naked female body. Nakedness, I feel, has such a broad discussion linked to it. Just by removing clothes, we can see nakedness in a thousand different ways. We can see it as vulnerability, or we can see it as power. We can ask questions like, is the figure naked for themselves, or are they naked for us, the viewers? Are they naked or nude? So, I do find it interesting to paint the naked female body, because it opens that discussion.”

Could you share with us what you might be working on in 2023?

“Yes! I am currently doing my BA in Camberwell College of Art (in London), and will be having a group show with my course mates in central London, at an art gallery called Bargehouse. It will be from March 7-13. So if you are in London and have some free time, come look at some cool art! I am really looking forward to it because I feel like my work has shifted ever since coming to London. It definitely had an impact on my practice, and I’m excited for what’s to come.”

VICTORIA HERTEL, 31, INTERACTIVE INSTALLATION ARTIST

Credit: Tan Yang Lin Jonathan

Hertel is a German-Venezuelan artist whose installations combine sensor technology, trace and motion to create immersive experiences. She relocated to Singapore for education in 2020, graduating with a MA in Fine Arts from Lasalle College of the Arts in 2021 and snagged the Chan-Davies Art Prize for academic excellence in her MA research.

Hertel has quickly become known for a growing body of work that integrates and piques people’s senses (beyond that of the visual), as exampled through the artist’s popular Steps (2022), a motion-responsive, light-based work installed at The Projector Golden Mile as well as her contribution Times (2023) to the ongoing group exhibition Bad Clocks: Alley Through a Pinhole at Objectifs, which consists of 12 brass bells that chime differently based on visitors’ interaction with the installation.

Credit: Tan Yang Lin Jonathan

Hello Victoria! Tell us about your journey as an artist. How did you come to art, and looking back, what have been the main sources of inspiration for you? Who or what has influenced your path as an artist?

“Art was a way to retreat into myself as a kid. I was able to enter my own world, especially when the external world became too taxing or overwhelming. I was always sketching or painting in my childhood and teen years and I knew pretty early on that I wanted to study fine arts later.

In terms of sources of inspiration there were of course particular artists and movements that informed my practice in different phases of my artistic career. I was trained as a painter and my references back then were large format gestural painters such as Cy Twombly or Gerhard Richter. As my practice transitioned from painting to sensory immersive installation art my resources shifted with me. First to dimensional painters like Angela de la Cruz or artists that worked with components of painting like Karla Black as well as artists at the intersection of painting and installation like Enokura Koji.

As my interest in spatial and sensory perception expanded I looked towards studios such as Olafur Eliasson’s or movements like Mono-ha. I feel like I still think about installation art through painting. My work revolves around traces, gestures and abstract forms of mark-making, which is painterly, just that it’s no longer myself creating these marks but rather others that trace along the canvas of space.

The most influential inspiration however comes from the conversations, writings and encounters with and by other creatives and mentors that I have experienced along the way. From the unravelling of ideas with others I gather fresh input, test the limits of my own notions and learn about life. I also enjoy reading and the knowledge expansion that comes with it. Political theorist and philosopher Jane Bennett as well as art critic Isabelle Graw have completely restructured how I view traces, matter and energy while the concepts of philosophers like Graham Harman or Bruno Latour introduced me to a different way of thinking about the relational meshwork everything inhabits and existence at large.”

Your website states that you are interested in material-oriented phenomena. Can you tell us more about this?

“At its most basic, phenomenology explores the way things are experienced, sensed and exist. It stems from an embodied understanding of your surroundings that sidesteps thinking for sensing. Not that one isn’t involved in the other but it addresses a more intuitive, bodily, sensorial way of making sense of the world.

There is an immediacy to phenomena that I find intriguing. They are linked to a sense of ephemerality and the dynamism of ‘becoming’ rather than more static states of ‘being’. I experience life as a series of interacting processes that are constantly shifting, so I try to conjure and channel this sensation of motion, agency and flow in my work. When I mention material-oriented what I am referring to is a focus on matter. I find the concept of everything, regardless of how minute, intricate, or complex it is, being composed of interacting particles and fields as substance matter fascinating.”

Credit: Colin Wan

Your works seem to all engage with people’s senses, one way or another. Was that intentional?

“We are multi-sensorial beings and don’t leave our senses beyond the visual at the door when we enter an exhibition space. A majority of works are highly visual, keeping the other senses of sound, touch, smell, taste and even extensions such as proprioception (the body’s ability to sense movement, action, and location) at a distance when taking in a work.

Through my installations I am working towards drawing attention and integrating other sensory experiences into the work. I am only starting out with this but I think it is a wonderful challenge to learn how to balance one’s desire for the visual with an integration of other immensely influential senses – for example, smell in itself is such a portal that can transport one into an entirely different moment.”

Your works also often have a kinetic or interactive quality to them. What accounts for your interest in kinetics?

“Life is very dynamic. Everything is in constant exchange with what surrounds it and I feel that kinetics reflect that agency or ability to interact and connect with what is happening around and within oneself. Kinetics, put simply, is the effect of forces on the motion of entities or actuated changes within a system.

It is this element of chance and change that interests me. How does the motion of bodies, all types of human and nonhuman bodies, interplay? How does that reshape an experience, a space or even a thinking process? This is where the interactive component that I strive towards integrating into my work comes into play.

Some kinetic works I have seen are fascinating to observe but there is a certain distance or chasm that is maintained between the work and the observer. For me, I want to situate the observer within the work, turning them into a collaborator and interactor within this meshwork of motion, sound, light, space and sensory influences – which to me resembles life.”

Credit: Lim Zeharn, Lim Zeherng

Tell us more about your ongoing work – the Bad Clocks: Alley through a Pinhole exhibition at Objectifs that looks at how people understand and define time. What was the intention behind your work?

“Time is such a fascinating phenomenon in itself and I feel that the exhibition (her work pictured here) highlights this. In preparation for the exhibition I dove into theoretical physicist Carlo Rovelli’s writings in The Order of Time and even though I cannot completely comprehend the loop quantum gravity theory that the book explores, this malleable notion of time emerged from it for me.

Addressing the theme of Bad Clocks which connotes a more liberated sense of timekeeping, I was looking to merge the familiar, linear and precise keeping of time with an approach to time that subtly shifts, emerges and unfolds through our encounters. We have all likely experienced how differently time can flow, depending on whether we are enjoying ourselves or just trying to get through something.

This paradox of the unwavering constant and dynamic relational aspects of time is what I was striving to bring out through the work (pictured) – when the sound installation is activated through visitors, it begins to emit a constant interval of chimes that slowly ticks on regardless of one’s presence within the work. As visitors weave through and around the twelve brass bells that make up the work however, a stronger, higher pitch emerges. This sound is particular to one’s own movement and speeds up or slows down depending on how you interact with it.”

What other shows or projects you might be involved in for 2023?

“I am working towards a couple of exhibitions which will delve deeper into senses like olfaction or the connection between the body and space but I feel that a major focus of the year will be on research and development. Time is a huge component in making installations because I often try to create works from scratch or expand prior works, making it intense to navigate short deadlines.

Experimentation and a process-based working method that gradually unfolds and adapts over the course of making the work is important to me. I have ideas for works which I constantly pivot depending on the provided space, theme and collaborators because to me having a very fixed outlook on how exactly the work will look disrupts the possibilities that can emerge in the making.

So a lot of the upcoming projects are making space and time to have the work unfold over a couple of months or even a year to be able to connect the necessary sensory, technological and conceptual research involved in constructing the sensory immersive and responsive environments I am looking to create.”