Samuel Xun

Samuel Xun, 29, trained as a pattern cutter. But, even when he was in fashion, the works he created were more like soft sculptures than wearable clothing. Over the years, he has pivoted into making art, but continued working with textiles.

“I like that tactile quality and that sense of familiarity – the fact that these are things we put on our bodies every day,” he says.

The shift in media came about because he is not the kind to do the same thing over and over again.

“I like to keep things interesting by continually experimenting. I try to put something new into something that I know so the end result becomes this mishmash of backgrounds and techniques. I feel like my sculptures are not necessarily what you imagine when you think of sculptures.”

Xun’s works are often pink and sparkly, consisting of abstract lines and curves that bring to mind the idea of tension and relief. They come with highly evocative titles, such as I’d Love To See You Fall Again and You’re Repeating The Same Mistakes.

Xun says: “Although they are abstract and open to interpretation, I use titles to lead the viewer somewhere and form some sort of empathetic connection. I like the idea of using wordplay to give an open-endedness to the work, and to allow the viewers to unload themselves onto the work.”

Israfil Ridhwan

Israfil Ridhwan's rich, moody paintings seek to present a new view on traditional masculinity. PHOTO: CHER HIM; STYLING: JEFFREY YAN

If there is one emotion that powers the work of 24-year-old Israfil Ridhwan, it is melancholy.

“I try to capture this state of mind, whether you’re reflecting on past lovers or the future or the feeling of wanting to leave,” he says. “It’s always about this sense of longing.”

His work is also unabashedly queer. His rich, moody paintings almost always depict nearly naked men. Though they are muscular, virile and what one might think of as conventionally masculine, Israfil paints them caught in moments of tenderness and sensuality.

Perhaps it stems from a place of attraction, but one also senses a much deeper questioning of that attraction.

“I think there is this Asian mindset of what masculinity is – you have to be big and strong and everything. I’m very skinny, and growing up, I was always made to feel like I was lacking something,” Israfil says.

“So, when I paint these very macho-looking men, it’s more about reflecting this idealised vision of masculinity. It’s to get people thinking, ‘What do I think masculinity is?’

“I want my work to be like a one-on-one idea exchange when people look at it. Sometimes, people ask me, ‘Do you do only queer paintings?’ But that’s not true.”

Andre Wee

Andre Wee’s love affair with all things visual started in childhood, when he discovered the work of Taiwanese-American comic book illustrator James Jean.

Today, Wee’s work has grown beyond the scope of pencil and paper to encompass all manner of 21st-century technology.

The 32-year-old has a bottomless appetite for the possibilities offered by technological advancements, and is currently fascinated with the liminal space between the traditional and the cutting edge.

“The last couple of years, I’ve been very interested in ways of presenting 3D objects and art as almost 2D. I love creating art in that in-between area, where your viewer questions, ‘What is this? Is this 2D? 3D? Is this traditional art? Is this digital art?’,” he says.

“In the way that a magician creates wonder, I hope to create that same kind of intrigue in my work – like, how does he do that?”

He also wants to move away from art which imposes its meaning on the viewer.

Wee says: “In school, when you study literature or art, they make you write what you think the author or artist was thinking or trying to portray. It always felt very black and white, and I didn’t like that.

“With my work, I don’t want to force my narrative onto people. I want to create opportunities for people to see the grey areas, to have space for them to create their own stories.”

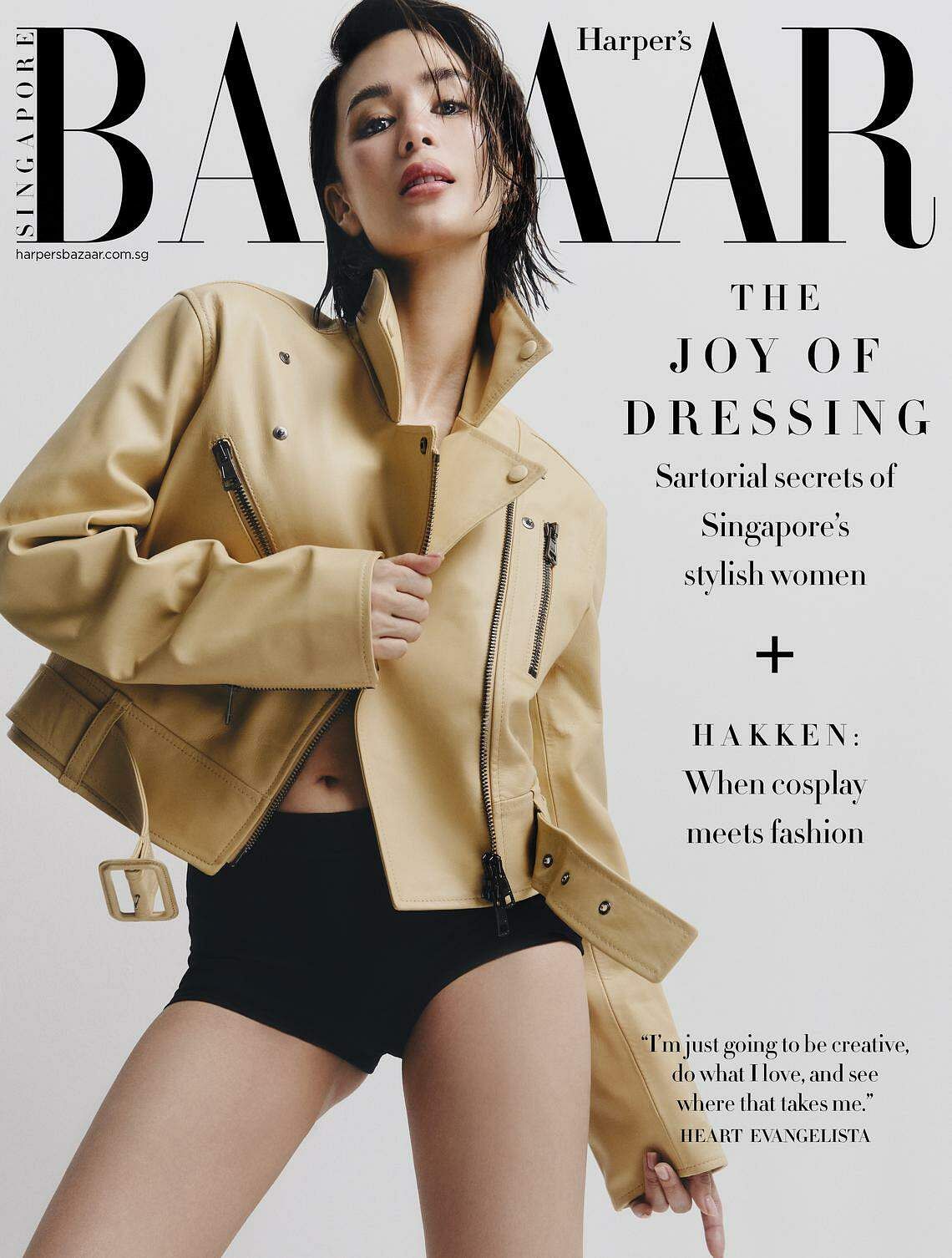

PHOTO: HARPER’S BAZAAR SINGAPORE