Shen Jiaqi, a rising contemporary Singaporean artist, has a creative journey rooted in her artistic upbringing and the challenges of pursuing art. After eight years of teaching, she left in 2020 to fully embrace her passion, marked by exhibitions at various galleries, including Cuturi Gallery, where she has found a supportive community of fellow artists.

Her work reflects Singapore's evolving identity, influenced by her experiences as a modern Millennial woman. Shen explores hidden labour, domestic roles, and women's historical narratives in Singapore's industrial past, blending personal and collective memory.

In this interview, Shen Jiaqi talks about her recent solo exhibition ‘Dioramas of Industry’ and shares her journey, her inspirations, and the meticulous research behind her evocative works, offering insights into how she visually translates the complex layers of Singapore's history and culture into contemporary images of its past.

Can you tell me about your background and journey as an artist?

I grew up in a household that has always been creative. My Mom was a ceramicist and my Dad worked in graphic design, so I saw the hard work of it all, I saw the downsides and the frustration. My Mom wanted to sell her ceramics and carried everything on public transport, because we didn’t have a car, so she carried everything to art markets by herself. And she had experiences speaking to galleries, clients, etc while trying to sell her pieces. So, I kind of grew up with that environment, and I knew that art-making is not an easy journey. But we like to do what we are good at, that's the problem!

I don't think you have a choice in this, if you're an artist, you're an artist. That's that.

That's the thing. My parents wanted me to be more self-sufficient so I became an art teacher after I graduated and taught for eight years in a secondary school. In the end, I decided to finally pursue my dream of being an artist. While I was teaching, I was also creating art for two to three years before I quit to get myself into the ecosystem and I showed at The Affordable Fair and at maybe two or three other smaller galleries. It was only by showing and asking and talking to galleries that I realised that every gallery has a different agenda, a different audience. After that, I showed at an art space called Coda Culture in Aliwal Street. The owner of the space was very open minded, very forward thinking and it was an independent art space that was supportive of us Singapore artists.

It sounds like it’s important to identify your place in the ecosystem.

Yeah, it was the right place to be and it opened up doors for me. Kevin (Cuturi) came to see the show and he was considering opening a gallery in one of the buildings nearby. So that was how the journey started. I remember when he managed to rent 61 Aliwal Street, he was so happy and excited, running up and down the stairs and telling me ‘Just look at the floors, look how beautiful this place is’. And I got it. So a group of us came together, and yeah, that's how everything got started. The year I quit teaching was 2020, I quit in April and I showed my series of works ‘Comfort zones’, in August. Luckily, I was able to have a smooth transition because of Coda Culture, and because of Kevin. I have done a lot of things that I would never have expected between 2020 and now.

You have a unique view of Singapore and the space around you. How do you interpret this and what made you start looking at this as a subject?

In Singapore we have a unique culture of living with our parents, and because of our limited space and cultural traditions, we are encouraged to. It led to our generation’s search for our own space, and a certain sense of belonging, that I've always been quite obsessed with. Like a lot of artists in Singapore, we all have the same experience of growing up in a space that doesn't actually belong to us. Even though it's our room, it's not really our room. And in a broader sense, throughout Singapore’s history, we have always been trying to make space for ourselves. We have always been trying to establish our foothold. We were supposed to be in Malaysia but it didn't happen and then we were suddenly alone. We are all trying to find a space for ourselves in the city and our city is also trying to constantly find itself.

How did you choose the specific narratives, photos and historic documents that went into your recent exhibition?

When I first started this concept, the idea was based around the individuals that exist within the architecture, but I wanted to have a focal point. So I used my own experiences as a woman, as a modern Millennial woman in Singapore, to find some common narratives that people can relate to. There are a lot of stories about hidden labour and about sharing mental load in recent media, and within my personal circles. Even today there is a struggle for the division of labour in the house. So I thought, OK, let's do something in this direction.

Pretty quickly I found that the concept of stable pay was started in the factories in the 1960s (a fixed amount that was given to the worker every month). Before that, it didn't exist and I was like, ‘That's surprising’ because that was the first time that women had any experience of a regular income. I always thought that freelancing was the modern way of working, aka gig economy, but no, freelancing was the general way of working before the introduction of a regular monthly salary. It was the first time this had happened in Singapore’s history and the women who worked in the factories were one of the first groups to experience it.

It’s so refreshing to hear the woman's voice, because it's so often unheard, especially in Southeast Asian art where women are usually portrayed as ‘exotic’. So it’s great to see a different type of women coming through in your paintings.

That's the thing. We have the typical Nanyang style with everything looking very lovely with the palm trees, and in the institutionalised galleries here we have those half naked women in Balinese paintings. Those women were not naked originally. If they're wearing their regular clothes, isn't it nicer to paint that than for them to strip? Art has a history of portraying Southeast Asian women as vulnerable, and for the male gaze. We just accepted that this was how women were perceived. So I became fascinated with how women were portrayed over the years.

Women have never been soft like they are in the paintings. We have always had to struggle for survival. We have always had to be the ones holding ourselves, and everything together. There is the misconception that Asian women are very soft which we know is not the case. So being able to pick up on that and explore identity in terms of the women of Singapore during the 1960’s and 70’s, I just found it fascinating because many would assume that it was men who built Singapore, when it was only a small part of the story.

So you spent time at the National Archives researching these women and the spaces they occupied.

Yes, and I listened to lots of audio interviews with these women because there's hardly any photographs of private and candid moments, and I spoke to people I know. My husband's Mom used to work in one of the plastic factories that started in this era. She worked there her whole life. Some of the women in those factories were very young, like 14 or 15, they’d work in the factories to pay for their brother’s school fees and they worked for up to 20 years. They managed to raise a whole family and support their siblings with their salary.

You managed to bring all these first-hand accounts into your paintings?

Yeah, it was a challenge because how do I translate that? Visual translation is always the challenge. And how do I not give too much away? Because I want people to be interested enough to ask more questions. So that was the challenge of the whole series.

How did you resolve that?

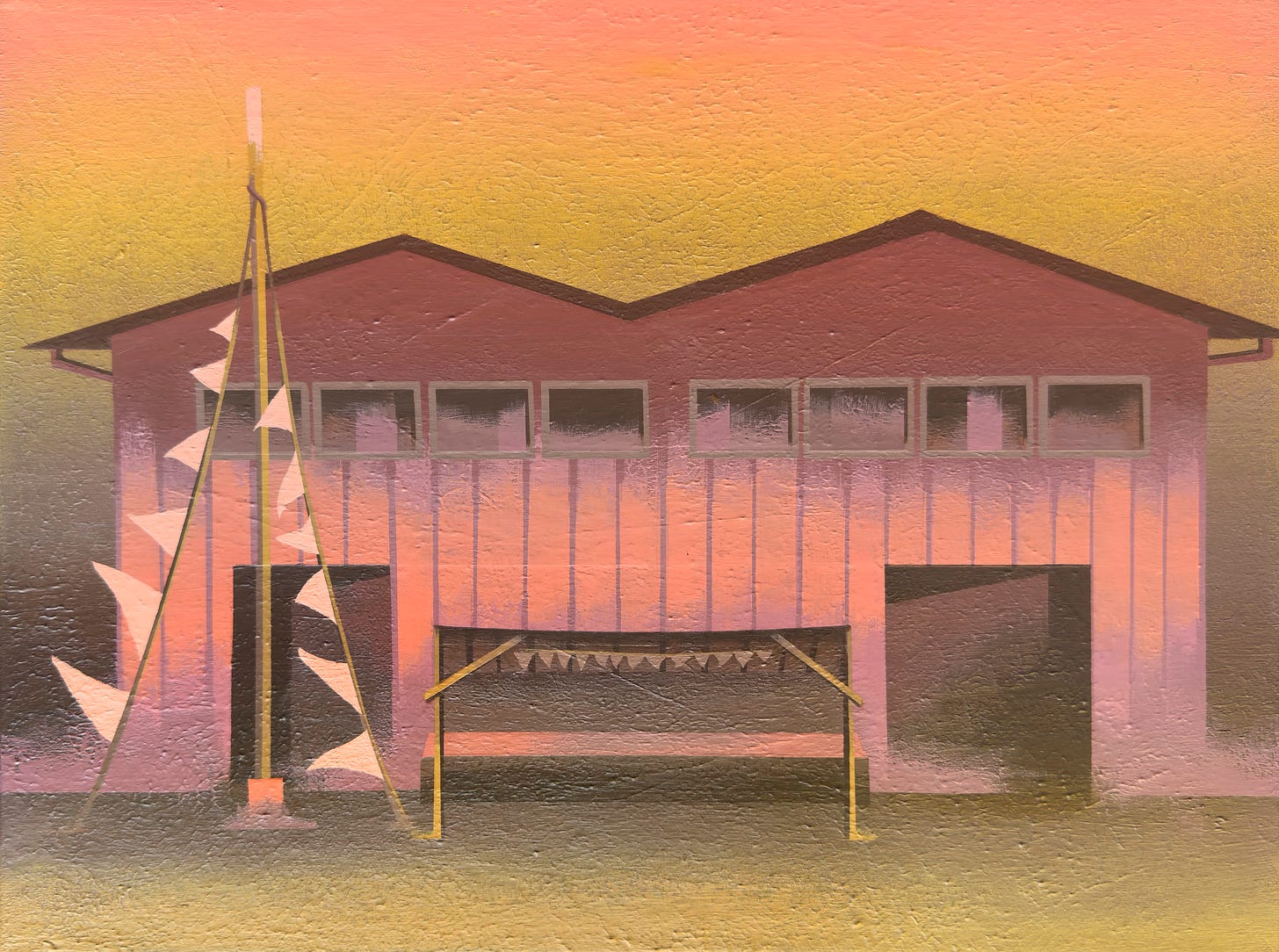

I started to focus on the Jurong area because it was a prominent industrial town during that era. I researched the homes and the environment of the women there. I took photographs at most of the sites although nothing much remains, but we do still have the Jurong Hill Tower. It still exists. It is a spiral tower that was one of the first things they built there in order to attract investors to the area, so they'd bring everyone up to the tower and show them what they could have if you invest. It was a viewing platform and it’s very distinctive because you could see similar architectural designs all over Singapore. They would walk the dignitaries up the spiral stairs, keep them talking, keep selling. It's designed for that purpose! Then there was a very famous Japanese fine dining restaurant at the top, so you get a nice reward after walking up those steps.

It's an amazing strategy and a big gamble because Singapore didn’t have a lot of space and investors needed to be convinced about the labour force but we were very lucky that the steel industry took a gamble and that was the start of it all. It was a very pivotal time, Singapore had only just split from Malaysia, and everything had to come together fast so this moment is part of Singapore's history right at the birth of the modern day, independent Singapore.

So you've got this information and you're starting to get an image of a time and a place and the people within it. How do you then start piecing it together?

I needed to find photographs to guide me through my telling of this story. It’s not that I want to paint these photographs exactly as how they were taken, but they serve as markers for a certain time, a certain kind of industry, and a certain story that I would like to encapsulate.

For example, in my painting of the TV factory, I knew that I wanted to show a communal memory. My parents were telling me that watching TV as a family was a huge thing during that time because it was the invention of the colour television. Everyone was excited about it because only a few in the whole stretch were able to afford one and everyone went to their house to watch, so the photo helps add to my narrative.

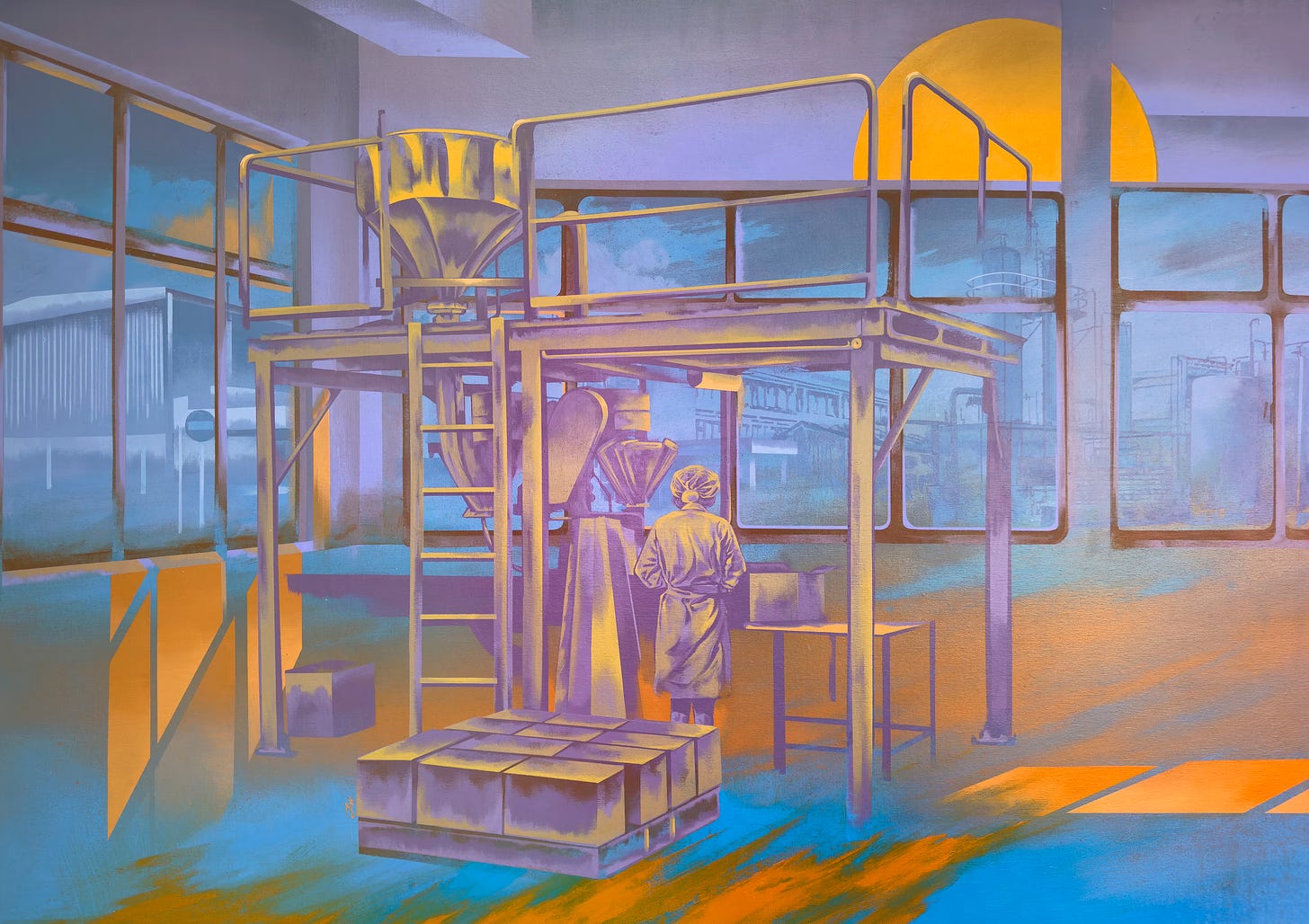

I also knew I wanted to paint the pharmacy factory. Singapore was producing Western medication despite it not really being accepted at first within traditional Singaporean culture, and I discovered that the factories also started the practice of shift work during those years. There was a whole power struggle in the news over how the factory workers were not willing to work these irregular shifts that would cause disruptions to their lives. As the issues were mainly raised by women, it appeared that the women were less cooperative, but it was because it was women who had to leave their children and homes to work these shifts, women must also bring the kids to school, and do the groceries in addition to the factory shifts so I knew I could talk about that.

Something I notice about your paintings is the fact that you're not objectifying these women, you're not inviting the viewer to gaze at them.

While creating these paintings, I experimented with what people look at. At first, I painted their faces and then I painted them working. It was a lot of manoeuvring around, wondering how I want these women to look because I don’t want the male gaze to be a distraction. So I decided to do their back view, they look like they're part of the architecture and I want people to know that she's working. Let's not disturb her. We are the visitors. We’ve been invited into their world.

Can you talk to me about colour? Because you have a very distinctive colour palette.

I use colours in a way to suggest emotions or feelings so the palette for these paintings needed to suggest a sense of nostalgia and memory. Like sunset and sunrise is the easiest way for me to explain it. When people look at a sunrise or sunset, we have this communal sense of knowing this beautiful thing is going to be gone in a few seconds and of the memory it’s going to bring. It helps imply that this is a stage in Singapore's past that's long gone.

So blending imagery and colours seems to blur the boundaries of memory and reality. Do you have that intention in your work?

Yeah. I use colour to suggest activity, to suggest that there is more to this painting than you can imagine and the viewer can fill in the blanks. So for me, colour is an invitation for that and I use it to emphasise that this is a fictional narrative based on the emotions I want in this painting.

Have you had any negative criticism? Have you had people expecting your paintings to be realistic or historically accurate?

As artists, we do have some leeway, but for me the key thing is to be respectful. And I feel like I was respectful to the details. I was respectful to the ladies, but yeah, I had some contention. There were people who were curious about the glass pieces I made with newspaper headlines of that era. They are the actual headlines of the Berita Harian newspaper and they used the Malay language. ‘Why do you pick Malay newspapers? Why not Chinese newspapers? Why not English newspapers?” were some questions that were asked. The thing is, at that time, a lot of the ladies either spoke dialect or Malay. There was also a lot of turmoil and stories about the Chinese language during this era that would deserve their own spotlight, separate from this show.

So, to the future! Can you now take a holiday?

No not yet. I am exhibiting at the Cuturi Summer Group Show and also thinking about the feedback from my solo show. There was a lot of positive feedback and curiosity about the smaller piece I did for the show which I am trying to dissect. I’m thinking about what other things I can do with a piece like this, this size and with this aesthetic and whether I want to continue telling the same story without it being boring for the viewers.

Final Question! Any advice to aspiring artists?

I would say consistency is key. I always tell myself that what I'm working on now is the work that I can produce now with my capabilities, but my best work could only appear in a year or two or even further in the future, because I'm still young, and still experimenting. Also, just don't stop, be bold and just keep going and keep practising so that you can build a solid portfolio, it’s more convincing for galleries than one masterpiece! Also, go and visit all the galleries and talk to people. The ecosystem here is small, so people are always looking for collaborators, and you might as well be familiar with how things work here.

Find out more about Shen Jiaqi’s work at the following links:

Instagram: @s_jq

Facebook: SJiaqi

Website: sjqart.com

Represented by Cuturi Gallery: cuturigallery.com