Can you give me some background to how you started painting?

I started with drawing. Art wasn't really in the family - my parents were both in STEM. But we'd still do weekend workshops for ceramics, chinese ink, dance, etc., so it wasn't discouraged. As a kid, I'd made a series of comics about made-up furball characters that my mother found amusing. I later got into designing characters, monsters and fantastical settings for a while. This led me to digital painting, then into other media later on.

When did you decide to focus on art?

There were two events that stand out in my mind. One was when I enrolled into a local animation programme. I learned a lot there, and it still informs a lot of the way I ideate and approach creative organisation. Another was when an elder cousin remarked on how I never seemed to draw anything else but dragons. It struck a chord and bolstered me to think beyond my comfort zone. I still think that dragons are great, but I have different tools now that resonate more closely with what I feel.

Specific to what I'm doing now, I'd say it was around 2016. I'd tried a couple things by then, but nothing really stuck. And, I don't know, maybe it had to do with hitting 30 and readjusting my priorities. I felt a conviction towards painting, specifically, in a way that I hadn't before. I just wanted to paint because it helps me feel deeply in a way that very little else does.

How would you describe yourself as an artist?

I became fascinated with Rothko's work in my 20s. I was sceptical of how he approached his paintings as something he felt more than saw, sometimes even forgetting pieces he had painted. I sought out a few of his paintings and considered them to be, at best, puzzling. Then I saw one at the Tate that made my heart shift. Between the colour vibrations, understated complexity, low light, silence, and scale, something intangible had emerged. I stood there with a knot in my throat for a long while before I had to head out. You can find meaning in that, or not. It seems impossible to explain to someone who hasn't felt that sort of thing, and I think that's really interesting.

I came to think of paintings as stacked objects in flat space, of layers of paint and metaphor, each one obfuscating the last, building up towards that intangible something. There is a mechanical nature to the process that is also informed by surrealist automatism, plumbing my subconscious for fragments of memories for which I feel an exceptionally strong empathetic connection with.

Gesture and movement have also come to form a broad basis of my visual vocabulary over the years. They are expressions of the human body and we understand them intuitively. Though my work in recent days has veered closer toward non-representational abstraction, it's still very much rooted in the language of the body as it is felt, if not so much in its image.

Ouroboros (2023), Oil and wax on canvas, 76 x 96.5 x 3 cm ©Yanqing Low

You’ve mentioned that Francis Bacon is also a huge inspiration. Can you explain how this feeds into your work particularly with reference to Ouroboros and Boundaries Green?

Bacon understood the figure, and the body's relationship to space. You see it in the way he plays geometric space off organic line and form, and I resonate with the liberties he took in depicting the body as an experience more than a thing. I suspect he drew excessively too, making studies and breaking down his compositions. I approached Ouroboros and Boundaries similarly, prioritising gesture and colour over form as the body falls away. The space is different - less flat but still flattened. Memory and trauma separated him from the advancements of the new world that were consuming his reality. His story was that of isolation. Today, it's all integrated, like soup - we're the tech, we're the product, allowing ourselves to be consumed. I pictured this skirmish playing out in our minds - a living computer where rationality and intuition do battle daily. So I arranged my compositions to reflect the rhythms of brain lobes.

Boundaries, Green I (2023), Oil and wax on canvas, 50.8 x 60.9 x 3cm ©Yanqing Low

Can you tell me more about your creative process? It sounds like your animation training is still part of it.

I still plan and ideate in a way that I learned then. I use sketches to prepare, toss about ideas quickly, and inscribe some intuition for the subject at hand into my senses. Besides that, I don't know. Maybe drawing out all those frames in minute iterations has left a mark. I'd have one to three frames between my fingers, rolling them back and forth to gauge the shifts in form in the frames to follow. It creates a ghost in the eye.

My earlier paintings explored this overlap as one motion transitioned into another until those rhythms took on a meaning of their own over time. I still see the ghost between the frames as I've moved on to something less literal. Animation is a process of making something out of nothing and bringing it to life. I suppose that like ghosts, the feeling that I chase in my paintings may only be as real as I believe them to be.

You're Still Here, Blue Velvet (2024), Pastel, charcoal, acrylic and watercolour on canvas, 61 x 61 x 2 cm

You use a whole variety of mediums and tools, can you tell me about this?

I enjoy working with different materials and seeing how they interact. They all have personalities of their own and speak to me differently. I've found that more unconventional tools produce less predictable and repeatable effects. I've also become quite particular about the surface of my paintings. I appreciate, more, the ones that bear the marks of the artist's thought process and struggles.

Soft pastel, for example, sort of shimmers in a way oil paint doesn't. It's basically pigment and powder. At its loosest, it's as if each particle reflects light at a different angle. It makes it hard to photograph, which endears it to me all the more. In a time where most pictures are only ever experienced through a screen I want to show that there's more to pictures than pixels. The virtual is not real, no matter how deep into the matrix you are.

The pink and red colours and the figuration in your recent paintings looks and feels very feminine. Is that something that you’re conscious of?

Someone else mentioned that recently. It isn't something I think about excessively. I'm curious, given that my past work has been described as being distinctly genderless. I chose those reds to accentuate the fleshiness of those forms and the menacing vitality of its space. But ideas live in spacial contexts; maybe femininity has changed. And, we're sacks of sensations. Maybe all these sudden aches and pains as I'm going into 40 are making me think about my body in a way I hadn't before, and it's coming out in the work. Who knows?

You say that your art reflects a mechanisation of the human condition. Can you explain why this plays such a significant role in your work?

Systems govern most aspects of our lives these days, with automation being the goal for most. Arendt (historian and philosopher) differentiates the tyranny of tradition from tradition itself, which when overturned, leaves its people unmoored from structures that before held meaning. All systems are brought to order through ideas that once were. They become overbearing when those structures become too rigid for people to exist within them because we've either grown beyond them, or we've forgotten why they even came to be.

Are we moving towards that inflection point as we rely on machines to do more and more of our thinking for us? We persist, as ever, in relation to our environments, chipping away at our problems with the tools that we make to get to the sculpture within the marble.

Is there a particular piece that you have struggled with?

I think it would have to be the one that I made in 2023 for my thesis. It was my first time painting something that large and there were some technical issues where the size of my tools were getting in the way of getting the marks and rhythms that I needed. Some of the colours that I had planned for weren't working as I'd imagined, and it was also a painting that lasted across a number of months, through which some initial ideas had changed. I was used to making alterations on the fly in a way that was more challenging on a large scale. But I learned my lesson, and the second one went much smoother.

Have you had any negative comments or criticism about your work and how have you countered that?

It wasn't a negative, more a word of caution. It was about the two bodies of work I recently built - one being more figurative, the other more non-representational. I was advised to focus on one, and I understand why. Building towards a meaningful body of work is a long and arduous process, and I appreciate the value of looking deeper, not further. But their ideation follows the same through road, and I had to make one to find the other. I've found my focus now.

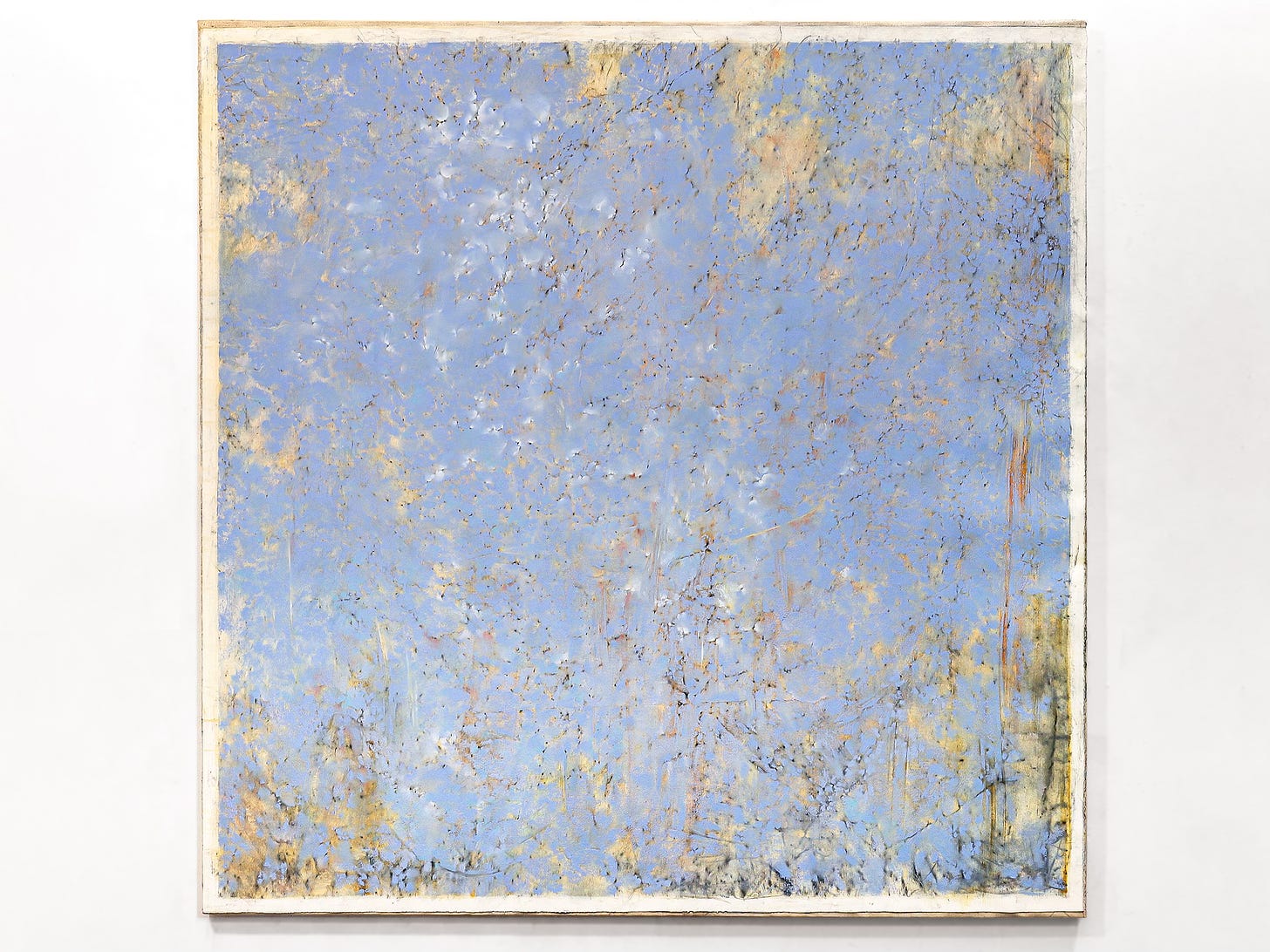

A Lament (2023), Pastel, charcoal, acrylic and watercolour on canvas, 140 x 141 x 2 cm ©Yanqing Low

Your approach to life is quite philosophical.

It's how I cope, haha. I'm a philosopher at heart, I suppose. Art is fundamentally a philosophy of aesthetics and of beauty and its counterparts.

Do you think having a gallery is important for selling your art?

It depends on your goals and needs. It's a business relationship that can be beneficial, or not. I know artists who don't seek representation and do just fine on their own.

Do you have any advice for emerging artists?

It's a marathon, not a sprint. Make friends. Compare less. Be kind. Find real reasons to make the work you do; don't chase the zeitgeist just because you think you're supposed to. And, work within your means. Invest your wealth, health and time wisely - we only get one chance at life, it should be about living.

CONTACT DETAILS

website: yqin.art

Instagram: yanqing.art